Nursing in The Great War

|

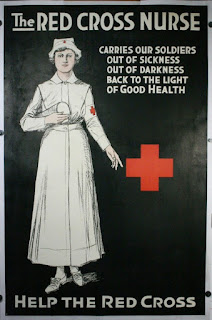

| Image courtesy of copyright IWM (Art.IWM PST 0318)). |

So often when we talk of war, we discuss the fighting, the aerial or sea battles and the men who fought so courageously for peace. What of the women? I've often read about the home front and of women who worked in munitions factories, or those drafted to work the land. But what of the bloody side of battle? What of the nurses and the thousands of women who went to nurse wounded soldiers overseas?

The Great War would bring significant change in so many ways. It was widely anticipated that this war would be short. Wartime propaganda began with a kick and helped to spread patriotic fever far and wide. Thousands of young men answered Kitchener's call to arms, but their fever was to calm very quickly. Once placed in the heart of battle the weeks rolled into months and then a year and disillusionment stepped in as many realised that all seemed endless, hopeless.

The wounded sustained injuries never seen before. What was worse was the lack of treatment available and the lack of expertise in treating specific injuries. It would become a time of pioneering treatment, a lengthy and innovative process which would continue throughout the years and into the next war. But aside from medical advancements and failings, what was life like for the thousands of women who answered the call to nursing?

Florence Nightingale made waves during the Crimean war and implemented great change in nursing care and practice. She was a revolutionary in her field and caused a stir back then, but it was worth it. Her efforts improved practice and contributed to saving the lives of men who would undoubtedly have died without her. Times were changing....warfare was changing....women were changing.

|

| Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons |

Women have always nursed. At the beginning of WW1, nursing was unregulated which meant that anyone could call themselves a nurse and offer their services. However, in 1919, this changed.

Life was very different back then. Women still did not have the vote. Few had jobs, but those who did or had to work would usually be employed in domestic service.

When WW1 was declared, women were keen to do what they could for the war effort, for their men and their country. In the beginning, women were asked to wait at home and "keep the home fires burning." It was generally anticipated that the war would be short-lived. Women from all ranks stepped forward and volunteered to work alongside nurses as Voluntary Aid Detachments - VADs. The VAD organisation began in 1909, and by the beginning of WW1, many VADs were already serving.

The war began brutally and continued, and by early spring 1915, both the government and military quickly realised the need for more workers and nurses. Women were then called upon to work in various roles, such as medics, farmers, teachers, munitions factories and VADs. The pristine, clinical image of the VAD dressed in her starched blue dress and white apron is almost a romanticised version of the reality they lived through. The work itself was rough, gruesome, dirty and undoubtedly shocking to many until they became accustomed to it. They were often exhausted, working long hours with little rest or time off.

The regime itself could be harsh with rules and procedures to follow, and heaven help those who wandered from the rigidity of it all!

|

| Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

The injuries the men endured had never been seen before - a consequence of changing warfare and of aerial battles. Medicine had not yet evolved well enough to cope with the severest of wound infections, and gangrene was rife. There were no antibiotics, and disinfectant was in short supply. As the war rolled on, medicines and dressings were running out too, especially in field hospitals at the front.

Of the existing qualified and experienced nurses, some had already seen war and its effects, having worked through the first or second Boer War (1880-1881; 1899-1902). Many nurses were eager to go abroad and nurse the injured at the front. However, the British Medical Military Services viewed female nurses as unsuitable for the front, presuming them unable to cope with the ugly face of war and so they were reluctant to send nurses to field hospitals overseas.

The British Red Cross formed the Joint War Committee with the Order of St John following the declaration of war on August 4th, 1914. The committee supplied services to the war effort while also organising nursing staff at home and abroad. It assumed control of the trained nurses and all VAD's and then proceeded to allocate them to the capable direction of Sarah Swift, the ex-matron of St Guy's Hospital.

In 1916, Sarah set up the College of Nursing, later to become the Royal College of Nursing, the professional body that continues to this day. Sarah was made a dame in 1919 for her services to nursing.

Between 1914 and 1918, around 90,000 male and female volunteers worked in Britain and abroad. The VADs carried out a range of duties from transport, organising rest stations, to patient care. They had to pass exams to achieve their first aid and home nursing certificates. The men were trained as first-aiders in the field and also worked as stretcher bearers.

One nurse, Violet Gosset, kept a diary of her nursing time during the war, something that was strictly forbidden. When her diaries were discovered in an attic many years later, they revealed the grim truth of what she had witnessed. She writes, “We had a fearful lot of head cases about this time as the tin helmets were not in use. Imagine a ward full of men with their brains oozing out of bad head wounds.” She gave accounts of life-saving amputations performed without the proper equipment and talks of "stretchers packed like sardines everywhere." However, it was not just war and its injuries which posed a threat but diseases such as cholera, typhoid, and tetanus.

Around 200 nurses were killed or died during the Great War.

|

| Edith Cavell 1865-1915. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. |

Notable voluntary aid detachment nurses who volunteered during the Great War :

- Agatha Christie – served as a VAD nurse at a hospital in Torquay. She said it was “one of the most rewarding professions that anyone can follow.”

- Edith Cavell - She is celebrated for saving the lives of soldiers from both sides without discrimination and aiding around 200 Allied soldiers to escape from German-occupied Belgium during the First World War, for which she was arrested. She was accused of treason, found guilty by a court-

martial and executed by a German firing squad on October 12th, 1915. - Vera Brittain – most famous for writing Testament of youth: an autobiographical study of the years 1900–1925. She became a VAD in 1915 and was posted to France in 1917.

- Enid Bagnold – author of National Velvet and The Chalk Garden. She served in London as a VAD.

- Clara Butt – superstar singer of the Victorian era, Dame Clara Butt lived in Bristol and was a legend in her lifetime, performing to packed concert halls all over the world.

- Violet Jessop - British ocean liner stewardess, trained as a VAD nurse after the outbreak of World War I. She had been a stewardess aboard the RMS Titanic when it sank in 1912 and was also aboard the hospital ship HMHS Britannic (the Titanic's sister ship) as a Red Cross nurse when it sank in 1916.

|

| Agatha Christie |

I gotta bookmark this website it seems extremely helpful very useful. Thanks for sharing.

ReplyDelete